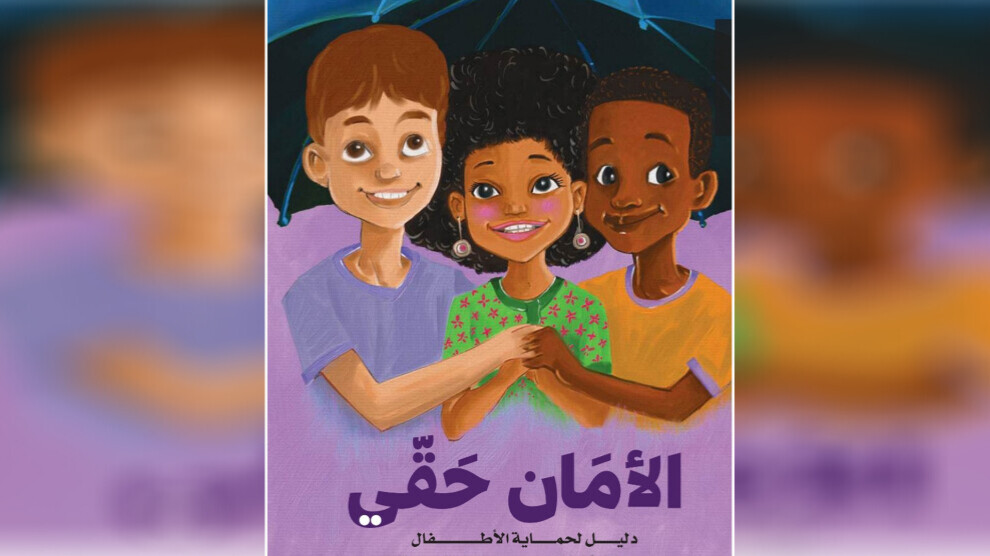

“Safety Is My Right” – An Initiative to Protect Tunisian Children from Abuse

To protect children from sexual abuse, the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights has released a guide titled “Safety Is My Right”, targeting parents and institutions working with children aged 6 to 16.

Naziha Bou Saidi

Tunis - As part of its ongoing efforts to monitor violations affecting the economic and social rights of women and children, the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights announced the publication of the guide “Safety Is My Right”. This initiative comes at a time when the Tunisian people urgently need comprehensive public policies that align with the country’s evolving legal framework for child protection and reflect national and international commitments to ensuring children’s rights to safety and dignity.

The “Safety Is My Right” guide represents a step forward in a collective civil effort to protect childhood amid challenging political, economic, and social circumstances — facing reality with courage, without fear, negligence, or delay.

Kholoud Faizi, editor of the guide, human rights activist, and expert in gender and human rights, told our agency: “As part of the Forum’s concern with monitoring social and economic phenomena, we noticed a rise in the number of children who are victims of harassment, and a major lack in educational frameworks and curricula that address children’s protection through awareness-raising methods that are neither shocking nor overly bold.”

She explained that the Forum asked her to prepare a guide for children aged 6 to 16. “We agreed to create two guides — one for ages 6 to 10 and another for ages 11 to 16 — because the way we address each group and the messages we send must differ between a 7-year-old and a 13-year-old child.”

Training and Awareness

Faizi clarified: “For younger children, the focus is on physical safety — teaching them how to refuse physical contact from anyone, even friends, because many incidents happen between children themselves or by relatives or adults. We also teach them where to go to report abuse and how to distinguish between a normal secret and one that must be shared with their parents.”

She added that for children aged 11–16, “the effects of sexual harassment are more serious. We teach them to differentiate between harassment and compliments, help them trust their feelings, and reject anything that makes them uncomfortable.”

Faizi stated that the name “Safety Is My Right” was chosen to emphasize digital safety as well. “At that age, children must learn about online safety — not talking to strangers or sending photos to anyone online. The guide is freely available to the public and can be accessed by educators and parents alike.”

She added that the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights will hold a training session from October 16–19 to train parents and educators on how to use the guides and encouraged educational institutions to engage with the Forum.

Faizi also mentioned that the guide respects Tunisian cultural values and can be used even with younger children — as young as four years old — by parents or kindergarten teachers. “It includes illustrated stories featuring family-like characters such as children and a grandmother, mirroring Tunisian family structures. The Forum will also ensure follow-up through additional training sessions.”

She acknowledged that discussing sexual harassment remains sensitive and often avoided. “It’s a difficult topic for educators or parents to address with young children, as they fear the child might misunderstand or that the language might be inappropriate.”

A Practical Tool to Help Children

She added: “Given these concerning realities, the Forum created this guide as a practical tool to help children understand their bodies and themselves, to teach them to reject any behavior or touch that makes them feel uneasy or unsafe. It aims to instill a culture of rights awareness among children and youth and to provide parents and educators with practical tools for prevention and protection from sexual harassment and violence.”

Faizi emphasized that the guide also encourages children to communicate with their parents, teachers, or any trusted person if they face a situation that threatens their safety. She explained that it was developed based on a human rights and gender-sensitive approach while ensuring it aligns with Tunisian cultural and social values. The content was simplified to be child-friendly, with materials tailored for ages 6–10 and 11–16.

It is worth noting that Tunisia’s child protection sector is under significant strain. The economic and social cost of violence against children was estimated at 2.6 billion dinars in 2022, while spending on prevention and victim care did not exceed 35 million dinars.

According to data from the Tunisian Social Observatory, violence against children represented about 2.15% of total recorded violence cases in 2025 — confirming that sexual harassment and abuse are no longer isolated incidents but a widespread social phenomenon requiring serious and courageous action.